James Garrity was a Clare County farm boy, the only boy in a family of four sisters. He was 19 years old when he convinced his mother, over the objections of his father, to join the Navy. James wanted to join his cousin, Arthur Looker, a Gladwin county resident, who had just joined the Navy. That was in Nov. 1917. In Jan. 1918, Arthur died of the flu at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Illinois. Jim Garrity died the next day. Both men were brought home by train for burial. Jim’s obituary described him as bright and cheery with a host of friends. It added that he was to have graduated from Harrison High School the following June.

Their deaths occurred before what is no called “the Great Flu Pandemic” had even gotten started. Peaking in the winter of 1918, this worldwide event would sicken more than a half a billion people, killing between 21 million and 100 million of them. In the U.S., about 28% of the population (then at 105 million) became infected, and 500,000 to 675,000 died. Deaths were especially high in young men, the group that included soldiers like Garrity and Looker. The flu became pneumonia and the buildup of fluid in their lungs, something Covid-19 does now, is what ultimately caused death. However, with this particular flu strain, it was those with the strongest immune systems who were especially vulnerable. As a result an estimated 43,000 American servicemen died, more than were killed by German bullets. Roughly 1 in 4 military personnel came down with the virus, and of those who did, 1 in 5 died. Death often came quickly, sometimes even within hours of the first symptoms. Congestion brought on by the flu built up quickly in lungs, resulting in pneumonia, which was the cause put on many death certificates of that period.

The Dec. 5, 1918 issue of The Clare Sentinel contained an article about Earl Green, a sailor from the small Clare community of Mann Siding, who told of how, while stationed in Boston, “he helped roll up 200 boys [soldiers] in sheets and carry them out onto the docks to be buried.”

Garrity was not the only Clare County resident killed by the flu. In total, 22 out of Clare’s 450 soldiers and sailors died from the flu, according to local historian Forrest Meek, author of Michigan’s Heartland, a history of Clare County from 1900 to 1918. Meek also writes that at least 59 county deaths were directly related to the flu (see listing from the book at end of this article). Clare County had only about 8,300 people at the time.

The Clare Sentinel during that period is filled with mentions of families and individuals coming down with the flu, battling the flu, recovering from the flu, or dying of it. There were also numerous mentions of church and school closures, sometimes for weeks at a time.

Public Service Announcement from October 24, 1918

Public service announcements warned of the dangers of coughing and sneezing in public and advertisements hawked products to those stuck indoors . In Michigan’s Heartland, Meek writes that doctors of the community worked overtime during the outbreak. Meek said that Dr. William Clute of Clare, hardly left his car for days. He had a chauffeur who took him on his calls and “those few moments constituted his night’s quota of slumber.” Meek wonders whether the fact Dr. Clute died at age 53 was partially due to his having worked so long and hard during this epidemic.

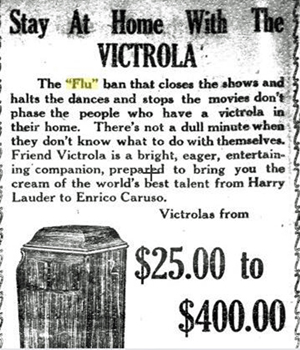

Advertisement in The Clare Sentinel from Nov. 14, 1918

Unlike now, there wasn’t a shelter in place requirement but then there wasn’t much of a need. Clare County was not a vacation destination at that time, there were no freeways and few good roads of any kind. Although people could travel by train within a state and across the country, travel internationally, other than war related travel, was rare. It was not until after the Second World War that regular international flights began to take place. During WWI, that meant what happened in China and other countries, including health problems, tended to stay in those countries. Of course, soldiers returning from foreign battlefields and lands could carry diseases back with them. But eventually the flu disappeared and Clare County, Michigan, and the world returned to normal.

James Garrity was buried in a small cemetery in Hamilton Township. A marker and an American flag mark his grave. His is a story more than a century old, but also a story that’s still relevant today.

Listing of flu deaths as compiled by Forrest Meek in his book, Michigan’s Heartland